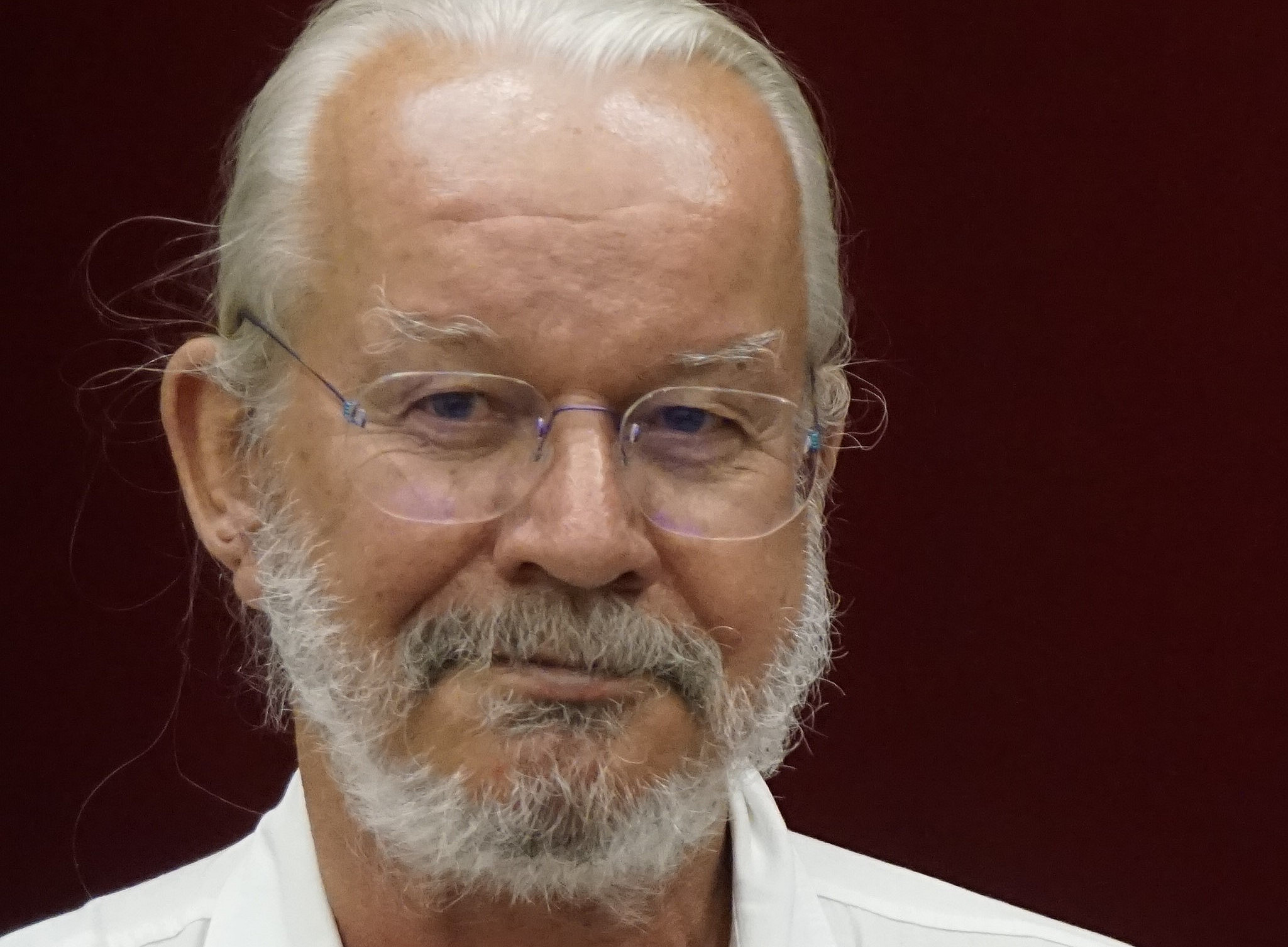

With the loss of Arnulf Rohsmann, art history in Graz has lost a brilliant and committed lecturer in modern art who was active for decades.

Arnulf Rohsmann already made a name for himself during his time as a student. As a student representative, he tried - it was the 1970s - to contribute to the dedusting of university operations and was immediately perceived by the teaching staff at the time as a serious discussion partner in both technical and organizational matters.

Even in his student days, it was clear to the unreserved advocate of an open art practice that academic preparation and mediation were central aspects of contemporary art. His commitment in this regard at the Neue Galerie in Graz - while still a trainee - inspired his fellow students and served as a role model.

While other students were still undecided or hesitant about a professional career - as I said, it was the 1970s - Arnulf Rohsmann completed his studies (which included philosophy, German studies and history in addition to art history) at record speed because he was convinced that he could only make a lasting impact in a relevant professional field. After his thoroughly successful activities in Linz (Nordico) and at the Carinthian State Museum, Arnulf Rohsmann found a suitable base of operations in 1987 as director of the Carinthian State Gallery. Here he was able to set striking and supra-regional accents with his exhibitions. Rohsmann's professional uncompromisingness and personal and political inflexibility probably led to a conflict with the then governor and cultural advisor of Carinthia, which resulted in a de facto withdrawal of his powers. At the time, this step was perceived as extremely arbitrary and unjust and led to many - unfortunately unsuccessful - expressions of solidarity with the person concerned, especially beyond the region.

As early as the 1990s, Arnulf Rohsmann was able to expand his field of activity through his teaching activities at the University of Graz (then also in Klagenfurt) and pass on his strongly theory-based understanding of modernism to students in a fruitful way. Through his habilitation in modern art history, this task was quasi-institutionalized and supplemented by supervising final theses. In his teaching, Arnulf Rohsmann set high standards, which he also demanded from his students; he did not tolerate non-binding and imprecise formulations in their written work. Not everyone always liked that. But those who accepted it were able to derive great and lasting benefit from it.

Josef Ploder