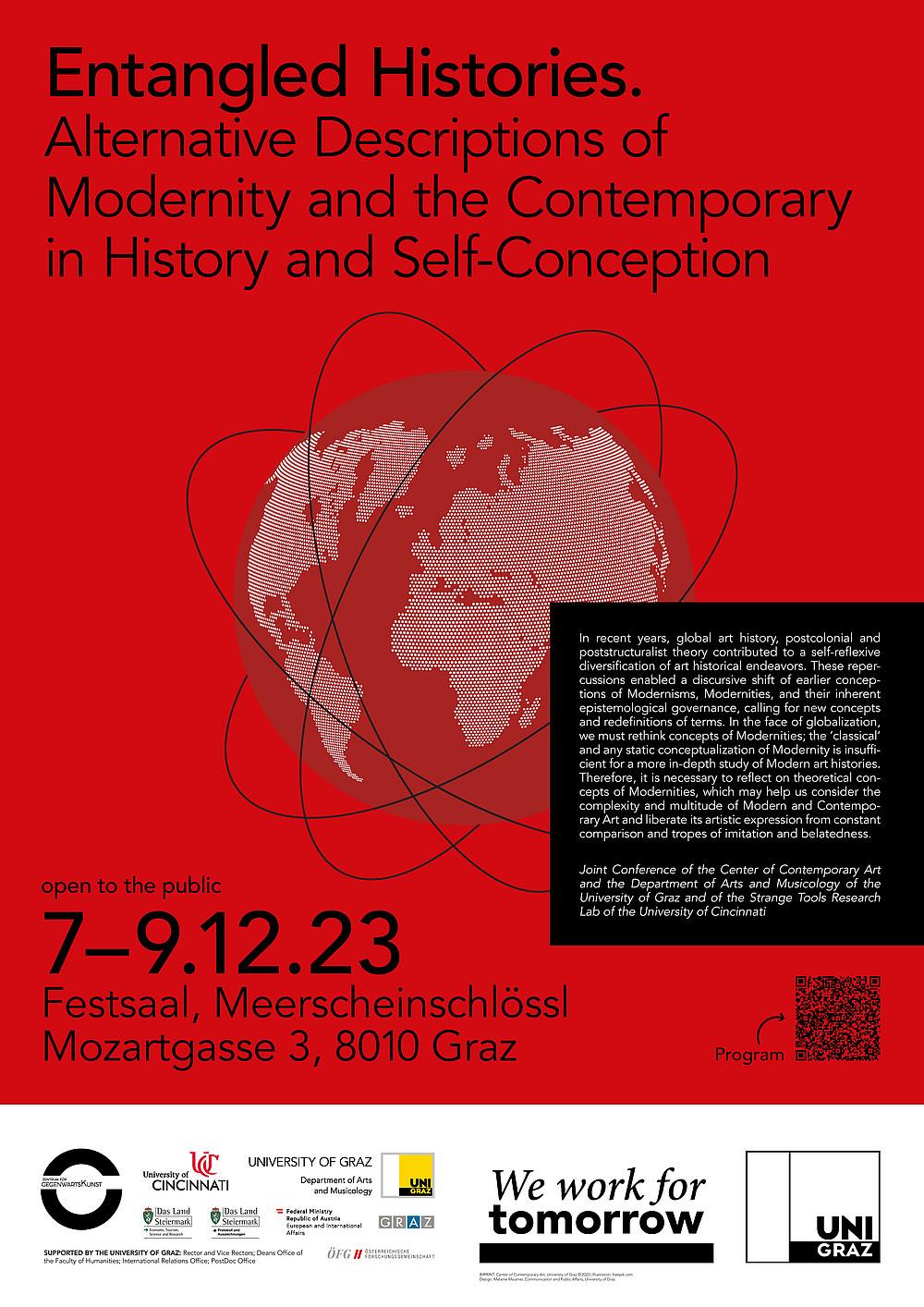

Entangled Histories

Alternative Descriptions of Modernities and the Contemporary in History and Self-Conception

Under the aspect of aesthetics, the aim is to explore how and with which manifestations embodiment occurs at all. The aspect of aisthesis aims to clarify how something can be sensually experienced and felt and how this process can in turn be perceived. For this research project, medium is negotiated from a double perspective: firstly, we understand the senses as a 'place of passage', i.e. as a medium - in order to show that it is precisely the sensory experience "through which objects exist in the first place" (Maurice Merleau-Ponty: 1994, p. 51). However, we then take this classical phenomenological approach, as first formulated by Merleau-Ponty, further to explain the importance of the arts for understanding theories of embodiment: for us, mediums are not only the senses themselves, which enable an understanding of the world, but they are in turn tied to media of embodiment, such as objects, scenes and scenarios of art. The general subject of this research project is the constitution process of phenomenal space and the subject in order to clarify the aesthetics and aisthesis of embodiment. The term "phenomenal space" here (in contrast to objectively measurable space) thus denotes a conscious, meaningful instance that arises in the process of experience and, through its emergence, forms the topological framework of this process.

Aesthetics, aisthesis and medium are intended as guiding categories for the project to help understand what thinking and perception actually mean. The project aims to clarify the question of how appearance, perception and transformation of embodiment are to be described, given that the question of what is embodied and how only arises through the act/process of embodiment itself. In recent years, global art history as well as postcolonial and poststructuralist theory have contributed to a self-reflexive diversification of art historical endeavors. These effects have enabled a discursive shift in previous notions of modernisms, modernities and their inherent epistemological violence, requiring new concepts and redefinitions of terms. Modernity is often defined as a specific way of thinking characterized by the rejection of the certainties of Enlightenment thought and religious belief. Modernity describes a modern way of life defined by the industrial world, urbanization and media technologies.

Modern art is characterized, among other things, by abstract art, montage, collage, non-linear narratives and the use of media technologies. In the historical analysis of modernism, the concept of "epochal thresholds" (Cornelia Klinger, 1995) is emphasized, which characterize modernism to the present day and were fundamental to the "cascades of modernization" (Hans-Ulrich Gumbrecht, 2002). Such an orientation indeed requires any critical view of the aesthetic category of the "modern" as well as the "contemporary" in art.

Methodologically, both a critical examination of one's own discipline and the thematization of the various historical, theoretical and artistic innovations in the field are important. This goes hand in hand with a changed concept of theory. Since the end of the 18th century, there have been historical parallels to this concept of the "modern"; it stands for epistemological approaches to objects that cannot be grasped with traditional methods of observation or categories of analysis and therefore require new ways of seeing and forms of access (think, for example, of the discipline of philosophical aesthetics founded by A. G. Baumgarten in 1750 and new forms of aesthetic theory formation).

Furthermore, in his essay "The West and the Rest - Discourse and Power", Stuart Hall examines the role that societies outside Europe play in this process. He examines how an idea of "the West and the Rest" is constituted and how the relationships between Western and non-Western societies have been portrayed. Hall writes that "the West" is no longer just in Europe, and that not all of Europe belongs to the West. The historian John Roberts argues that "Europeans have long been unsure about where Europe 'ends' in the East. In the West and to the South, the sea provides a splendid marker ... but to the East, the plains roll on and on and the horizon is awfully remote" (Roberts, 1985, p. 149). Eastern Europe does not (yet? has never?) really belong to the West, while the United States, which is not in Europe, definitely does. Today, Japan is, technologically speaking, Western, although it is 'Eastern' on our mental map. By comparison, much of Latin America, which is in the Western Hemisphere, is economically 'Third World', struggling - not very successfully - to catch up with 'the West'. Hall notes that "the West" is an idea rather than a geographical fact, so "the West" is a historical rather than a geographical construct. He concludes that the meaning of the term is virtually identical to "modern".

Furthermore, the curator Okwui Enwezor takes a critical stance towards the idea of proximity to "the West" as a paradigmatic interpretation of non-Western modernism, as this idea contributes to the depoliticization and decontextualization of art production. Instead, Enwezor proposes a "postcolonial response" to the emerging fields of global modernisms, as "in its discursive proximity to Western modes of thought, postcolonial theory transforms this dissent into an enabling agent of historical transformation and thus is able to expose certain Western epistemological limits and contradictions." (Okwui Enwezor, Manifesta Journal, 2002, p. 113)

This observation leads to broader questions: How can we redefine the concepts of modernity and modernities? How can we write the history of modernities while being aware of the " darker side of modernity " (Walter Mignolo, 2011) such as colonialism, imperialism and universality? The fundamental notion of Western modernity as a universal norm is based on the problematic and paradigmatic assumption that "the Modern is just a synonym for the West", which often understands modernity as the intellectual property of enlightened Europe. For non-Western countries, this means that "to become modern, it is still said, or today to become postmodern, is to act like the West", as Timothy Mitchell explains. (Mitchell, 2001, p. 1.) In the face of globalization, we need to rethink the concepts of modernity; the "classical" and any static conceptualization of modernity is insufficient for a deeper investigation of modern art history. Therefore, it is necessary to think about theoretical concepts of modernity that can help us take into account the complexity and diversity of modern and contemporary art and free its artistic expression from constant comparisons and tropes of imitation and backwardness.